University of Arts in Poznań

Satyrykon: Three great professors (Eugeniusz Skorwider, Mirosław Adamczyk, Grzegorz Marszałek), well-known poster creators are patrons of his year’s “Sharp Eye Skills”. Does this mean that we might mostly see posters at the exhibition?

Szymon Szymankiewicz, the member of professor Eugeniusz Skorwider workshop at Poznań Art University: You can expect quite a big variety as far as the form and topics are concerned. The works presented come from the two workshops of poster – prof. Eugeniusz Skorwider’s and prof. Grzegorz Marszałek’s as well as from prof. Mirosław Adamczyk’s workshop of illustration. Thus, there are posters and illustrations relating to current cultural, social and political events, commenting in sophisticated way human condition in today’s world. They all share a common feature which can be defined as a specific kind of shortcut in thinking and meaning captured in a graphic form.

Five-year-long history of this cycle is a lot and I’ve got impression of observing some change. In the introduction to the exhibition you don’t emphasise the title-present sharpness and its expression any more, provocatively mentioning such classic categories as pleasure, learning and social function of art. ‘These works are brave enough to bring the pleasure and teach’, says professor Roman Kubicki, a philosopher. Some viewers may feel happy but other may feel scared… Is your edition of “Skills” losing its sharpness and beginning, far be it from us, to mature?

Quite many works present complex, sometimes difficult and serious content served in a funny, perverse or intriguing form in order to reach the viewers and easily make them reflect. We’ll meet young artists’ freedom of thinking and interpretation in showing different viewpoints and ways of treating particular topics.

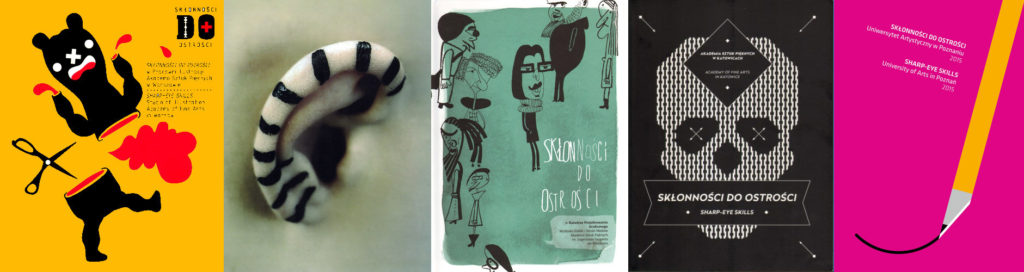

Catalogues accompanying these exhibitions traditionally have differed from typical ones. Warsaw Fine Arts Academy, starting the project, Wrocław, and lately Katowice Fine Arts Academies, they all promoted unbounded with any editorial habits or ‘market rules’ freedom. The last catalogue was in fact a kind of self-publishing manifesto (its introduction spoke with language of artistic manifesto as well). What is it going to be this time? Are the skills of “Sharp Eye” going to be present only individually, in particular works or in edition sphere too?

For example, for this year’s edition there has been designed a graphic motif which will appear on the catalogue cover. It depicts a hybrid of a pencil and a scalpel cutting a form of arch resembling a smile. The motif is our interpretation of the exhibition title, but at the same time it is a metaphor of what creation of ‘sharp’ graphic comment may be.

Roman Kubicki

Pleasant lessons of democracy

This is neither the time nor the place to spin metaphysical reflections about art, reach for cultural entrails of its origin and conditions of its existence. Art has the courage to be ever difficult, which does not mean it presumes the logic of renunciation or resignation. Art can be difficult both when it distances us from life and when it tries to seduce us with our own existence. Without this effort culture becomes barren; in such barren culture life can only drift. Joseph Addison, an English aesthetician (1672-1719) wrote: A man of a polite imagination is let into a great many pleasures that the vulgar are not capable of receiving. He can converse with a picture, and find an agreeable companion in a statue. Not only is art the source of pleasure, but the ability to perceive it helps distinguish the cultured from the common boor. Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1749-1832) was also convinced that all the arts have a double goal: they should give pleasure and at the same time instruct.

I quote these two fairly aged statements, because they both encompass well the works presented in this cata-logue. The sensation of pleasure as well as conviction, that yet again it was possible to see something differently, both create the evoked experience. The works, which all seem to have in common the trust in the sense of humour, irony and the difficult faith in a human, that have the courage to please and-because it is a pleasure we gain not only from looking, but also thinking-and to teach. To teach, and not to instruct, as Winckelmann wanted.

The connection of art with the realm of pleasant sensations deserves attention. Thanks to the hedonistic aesthet-ics pleasure is no longer the uglier sister of the so-called major values, which founded each conception of a decent life. Somehow the aesthetic –and thus sensual-pleasure had to be smuggled into the ethically legal salon of social-ly overt life. The world, once exclusively populated by sinners, is now occupied mostly by wonderful people. Sin is no longer the main figure of human fate. Body images in particular become signposts, which more and more often show the way to the body itself. The ideology of ascetism fits neither a democratic nor a consumptive society.

Advertisements are the banners of consumer community, banners, which – trying to increase our appetite for life-tell us nothing about our vanity, but consistently remind us that we deserve something and we are worth some-thing. In a consumer community the only thing deserving to exist is what will vanish soon: it is all about not having something only to want it again. Who wants to open up to another something must have the courage to recognise oneself in what will soon stop existing. It is not the existence that avoids questions about nothingness, but rather nothingness turns out to be-probably for the first time in human spiritual history-Procrustes’ bed of existence: the only thing that deserves to exist in our life is what has the courage to seduce us with hope, that it will allow to be swallowed by the insatiable nothingness of the past. That is why love, whose light makes it impossible to see its end, loses to romance, which always openly heads towards its end.

Although a citizen of a democratic society should be aware of his worth and strength, that conviction should not grow on the soil of cheap compliments we are so generously bestowed by advertisements, but must be the fruit of his meditative and critical presence in the world. In a democratic society authority should not reproduce itself (as it did in non-democratic communities), but it should be established through elections of politically and socially active citizens. Yesterday’s tributaries must today feel worthy enough to make the choices. We need the self-esteem, as it guarantees the dignity of a democratic society subject. It is no wonder, that human greatness

and dignity has been emphasised more and more often in art, philosophy and literature since the renaissance. Its images are decreased of guilt and increased with the feeling of importance. It is the man, who creates himself to the image and after the likeness of the community he can-and wants to be responsible for.

Art preserves the world even when it radically distances itself from it. When art breaks away from life, it does so always according to the logic of Jonas’ escape from God’s voice. Attempts to free himself from God were vain, as Jonas made them always within bounds of his faith. Similarly art cannot free itself from life. The presented works of young artist from three studios of professors Mirosław Adamczyk, Grzegorz Marszałek and Eugeniusz Skorwid-er are not affirmative advertisements promoting ephemeral ideals of consumer society. These works enquire-with a witty sense of humour-about the threats lying in wait for the man anxious to have an intense relationship with the society. It is the man, who emphasises his civil vigilance and social and cultural activity. Authors of the works watchfully observe themselves and the world; it may happen, that having put on a noble ring of Gyges or a slightly clownish cap of invisibility, they abundantly draw wisdom from the gift of peeping. They are the perceptive mas-ters of precision; they accompany political and social contexts of our lives (e.g. posters ‘Myth of Europe’, ‘Prisoner of Conscience’, ‘Global Crisis’, ‘Multi-culti’, ‘Young Energy for Europe?’, ‘Poles Can Do It!’, ‘ More Culture’), as well as artistic events (e.g. cover designs ‘Lost Highway’, ‘Decameron’, ‘Macbeth’, or film and festival posters, e.g. ‘Sexmission’, ‘Jazz Jamboree’, ‘Traffic Police’, ‘The Mighty Angel’). They are not afraid to ask our contemporaneity bitter questions. At the same time they manage to avoid cheap intellectual martyrdom and boorish, metaphys-ically shallow affirmation of fate. They do not escape from the world, but-like Antaeus, the mythical giant, draw from it inspiration and creative force. Their works inscribe well into the culture current of drawing pleasure just from the fact that it is possible to take responsibility for one’s own life.

In the light of these works nothing is the same. Things and situations created by the works in connection with people gain new meanings. The difference stimulates and inspires as well as puts up resistance to our interpreta-tional habits. It is a well-wishing resistance, because it is wise. The only creative meetings are the ones which limit us, oppose our beautiful need for freedom to be faithful to mostly what has already been. Each contact with art contains a certain consent to difference in our lives. Art always sees differently. Art remembers differently too. And-what is most important-art wants to see differently and wants to remember differently. Art in particular proves that there is no such obviousness that cannot be formulated in a different way – to look differently, to touch differently, to think differently and to remember differently. In spite of the fact that art has always been brave enough to be difficult, we still cannot tame the mystery which is the source of that bravery. There is never enough of the legalisation of difference. It is worth remembering, when we try to convince ourselves that ques-tions – like journeys – educate, because they show a different life. Who asks the way goes astray differently! The more ways to live appear on his stage, the deeper and more humble becomes his approach to it. At least this is the reason to meet the works of the young Poznan artists.