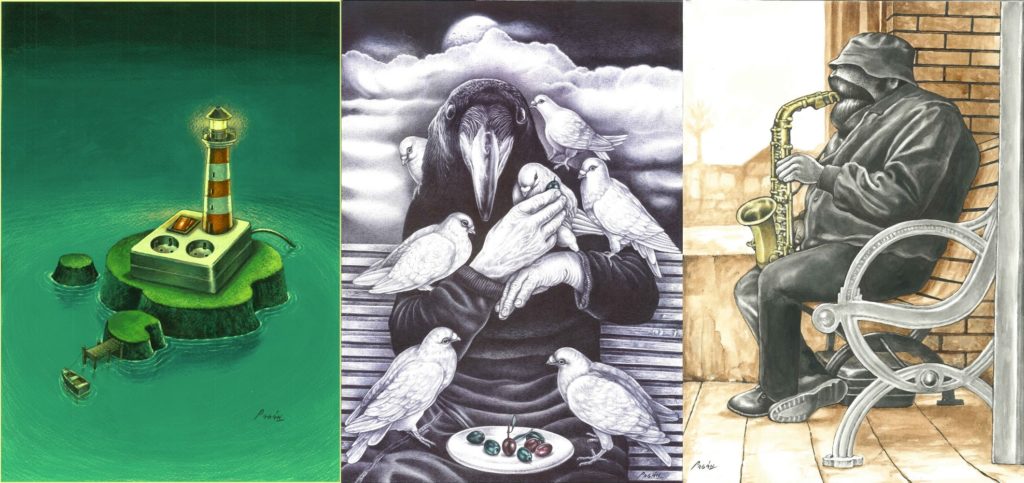

In the awarded by this year Satyrykon work a raven and a toucan are meeting beak to beak. It is a motif of a reflection which creates or demystifies illusions about ourselves – we know it so well indeed. However, this selfie, an extremely easy act of self-creation which has become a symbol of our times, reflects much more than just an individual. We can see continents, points of compass, culture, perhaps even featured social classes. A visually humble but very ambiguous, demonic among others, symbol versus an equally intelligent but more beautiful and more friendly(?) exotic counterpart. This confrontation is obviously comic, still it seems to be only one of the possible aspects. The polysemous accuracy of this juxtaposition, with its authentic and justified pride of one’s own tradition on the one hand, and on the other taunts about superficial swooning over “exoticism”, shall better be considered individually. Anyway, it is hard not to think about the artists’ pungent irony. Including self-reference reflection over his own artistic works.

Reynaldo Pagán Ávila is well-known across the world. He entered the world of European satirists also with a thrust. Although he have stayed in Spain no more than a few years, he cannot be described as “new face”. A similar name Young Faces (Cara-jo(venes]) was given to an artistic group he founded once in Cuba with his fellow students. In the defining its identity manifesto they declared the commercial aspects of artistic creation also mattered though the most important were ideas expressed by means of their paintings. And it seems that the artist is successful in combining these two aspects.

In the texts promoting exhibitions he is sometimes called “one of the leading contemporary Cuban painters”, he does not belong to the generation who had to paint on the walls or sugar and flour bags out of their ravenous hunger. He studied and later also worked at the Rafael Tejada Academy, but the studies disappointed him. The most he learnt by himself. He has drawn and painted since his early childhood, he has looked through books and copied as he believed then that this was the best way to learn techniques. And this is clearly seen in his works.

The American art patrons and collectors who came to Cuba against all odds would complain about Reynaldo and his colleagues painted as if nothing new had happened in art for decades, they were still emerged in Surrealism, Cubism, Expressionism, etc. They could have noticed however, the untold riches of talents. And their special attention was paid to Reynaldo Pagán Ávila, among others.

No doubts, he is an extremely hard-working artist. On the Internet, next to his impressive and various artistic output and reviews, we are able to find films from his Cuban times. They introduce Reynald in his natural surroundings, at work, and they feature a lot of his statements. Some of them confirm stereotypes. He talks about music as one of his key inspirations, about the meaning of vernacular tradition, about sense of humour and joking skills as the Cuban national character foundations, which serves as the defence against every-day troubles…

He cares deeply about his shows being different every time. He willingly experiments, and gets bored quickly. “Topics are like life – they are born and they die”. But they are also like love. When he proceeds a new work, he makes documentation, reads, looks for inspiration in pictures, words, sounds, tastes and scents, as long as he feels a complete identification with it. All the effects can scarcely be included in one piece of works. Therefore cycles come as a natural consequence. Although it is really difficult to fight the impression back that many of the works are merely sketches which aim at one or two most important paintings. The titles are significant. In most cases these are the base as the idea explanation, and looking for a pictorial equivalent is the greatest difficulty. However, the artist is quite experienced in this sort of “translation”. Let us consider divertimenti. This is an experiment, undertook by Reynaldo and his friend, of illustrating thoughts of a certain Cuban poet. One can spend pleasant moment indeed while deciphering picture nuances filled with humour, posing questions about dependences between personalities, epochs and environment.

If we stop for a moment at a metaphor of love, Reynaldo Pagán Ávila is someone between Casanovą and Don Juan. He has had a lot of love affairs with various subjects and techniques. To be precise, he has transformed the biggest part of world history and world painting, and presented it from Cuban specific perspective. Secondary flirts with the art of East or “colonised profiles” painted with coffee, are only two examples of his inventions. The greatest value of his paintings is perhaps the fact that they exceed far and in many ways the ideological, journalistic contents, in any case, willingly explained by the artist.

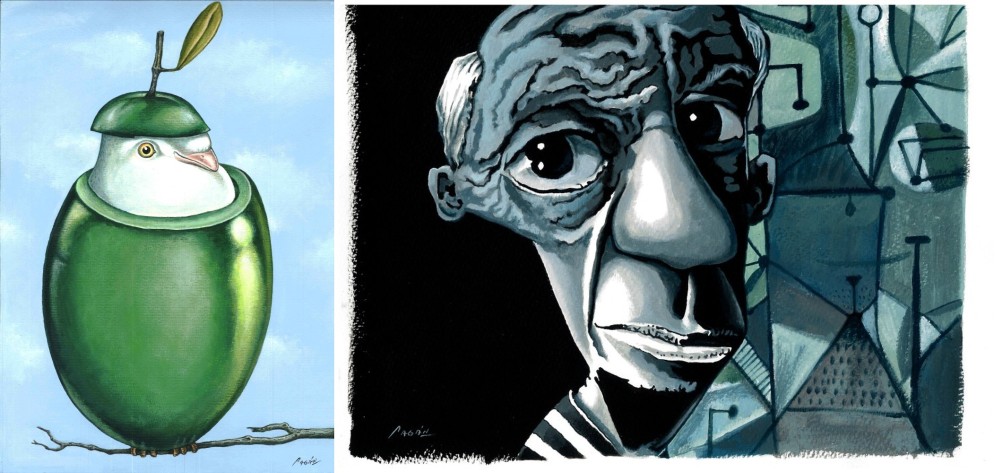

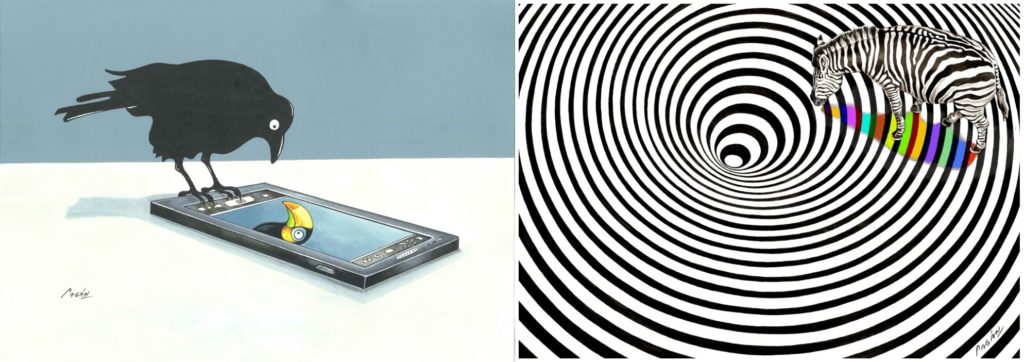

The recent film, published on YouTube, introduces many of the works shown within our exhibition in a manner of single frames. It is a sort of “documentary” of what has happened lately. Successful participation in various contests – we can recognise the olives immediately…, quite recent cycles, Black and white and Tauromachia. We can deliberate whether Picasso in a Breton telnyashka is a humorous joint element, a common part of sets or just another topic. This is an evidence of a constant quest which cannot be perceived simply as evolution of some kind. Perhaps, his recently less brighter palette has resulted from the subjects he has taken up… Actually, Pagán’s artistic language has changed since he moved, it has become more lapidary and accurate, or perhaps it has resulted from his concentration on satire? Anyway, after having seen thousands of pigeon-and-grenade sets, it is difficult not to be delighted with both sinister and playful armour made of an olive, a question about the nature of a saxophone player’s hunger, and an expression of Picasso’s eyes in one of Reynaldo’s caricatures. It really is worthy to stand all these deliberations about cars, prison stripes and yards, as they lead us to such a flare-up of imagination, as the one with a zebra staring at hypnotic circles. Deep in his soul Pagán has remained similar to old masters. In terms of formal mastery, humility, an appetite for “studying”, and indifference to the question of originality. He is similar to them also in his skills of playing in all the areas, his preference for illusion, organic-mechanic forms, paradoxes, jiggling with styles; depriving people, objects and quotations of their natural contexts, only to confront them beak to beak following his own unexpected concepts. He often does it with primary passion only to bring back our sensitivity which has been dulled recently. But first of all to arrive at essence steadfastly, and ask questions about changeable and unchangeable nature of people and things. La mona aunque se vista de seda?

Beata Zborucka